Lionel Terray (1921–1965):

a life brushing the summits

He is one of those people who leave an indelible mark in History. Lionel Terray is undeniably of that caliber. Without being more destined or predisposed than anyone else, he devoted himself body and soul to the mountains while being fully aware of the risks and perils of such a life.

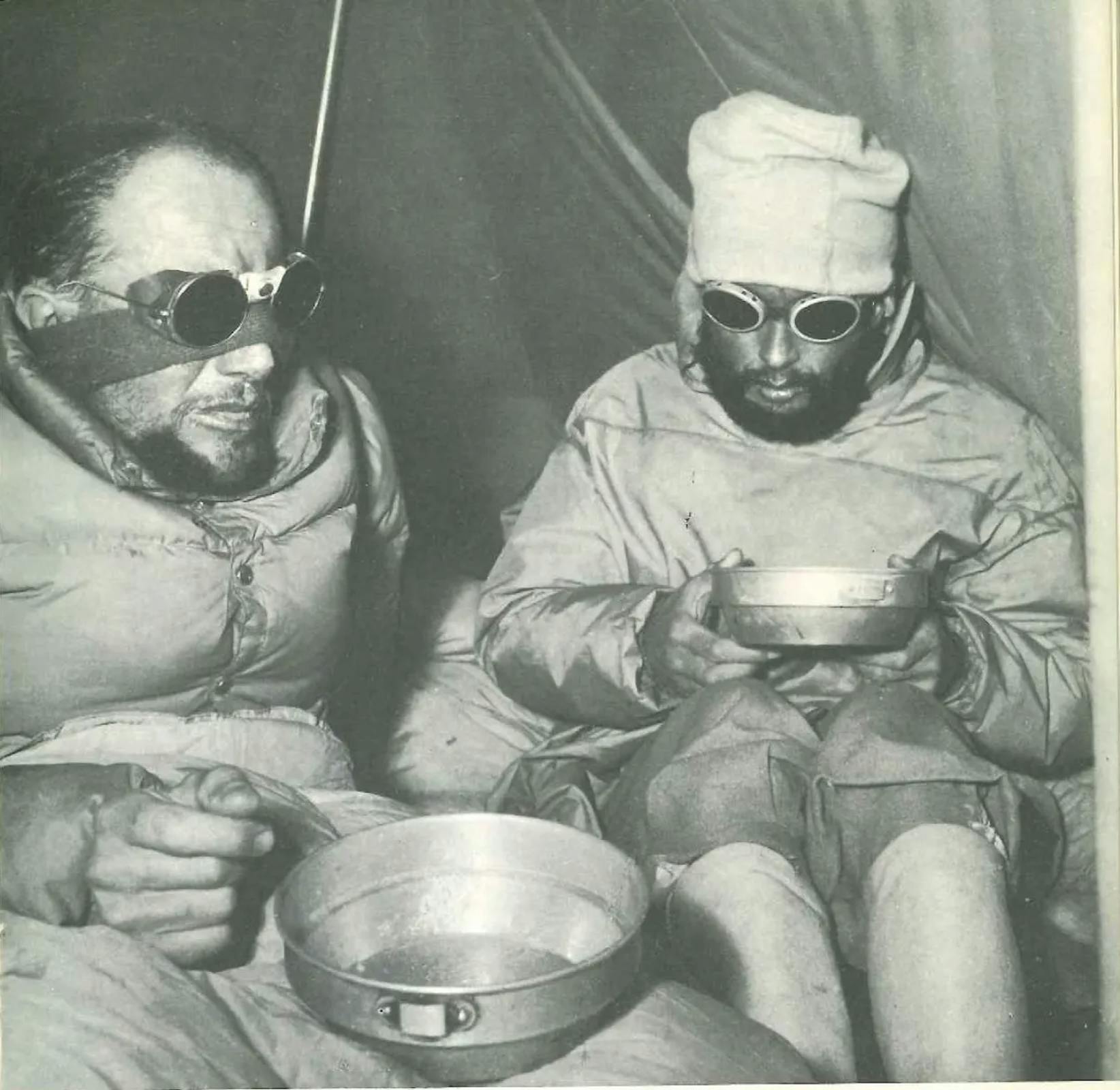

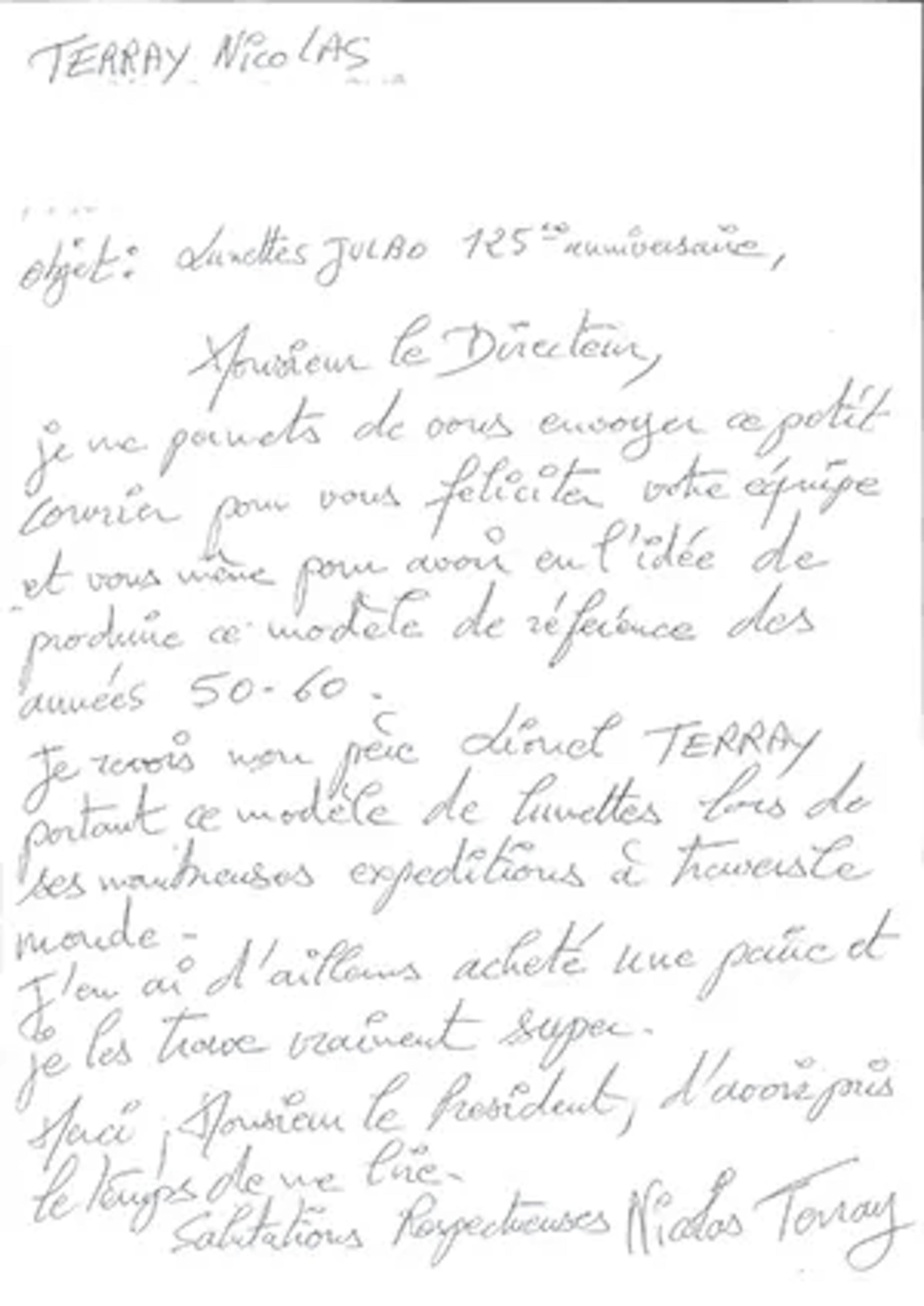

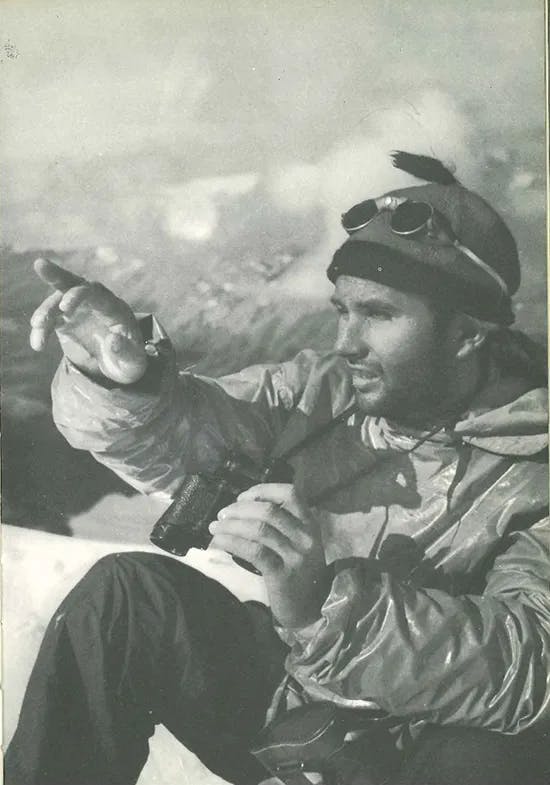

When we reissued the Vermont Classic for the brand’s 125th anniversary, Nicolas Terray sent us a touching letter. "I am taking the liberty of sending you this short note to congratulate you […] for having had the idea to produce this iconic model of the 1950s–60s. I remember my father, Lionel Terray, wearing this model of sunglasses on his many expeditions around the world."

Nicolas, now a ski instructor and mountain guide, who was only 7 when his father died, tells us that he is still struck today by his father’s popularity. "I went to Patagonia to see Fitz‑Roy with my own eyes, because you have to be there to understand what that feat means and people there all remembered my father and his expedition—he still enjoys great renown. It was very moving."

He continues: "Today, I still take pleasure in keeping my father’s memory alive through lectures and meetings. In fact, once when I was at the Annapurna base camp, some Japanese, having learned who my father was, handed me a version of his autobiography translated into their language: Les conquérants de l’inutile! Never would I have imagined the scope of his story."

Through the autobiographical novel—now a classic of mountain literature—and our conversations with his son, we became interested in the man who was Lionel Terray.

I remember perfectly that when I was a little boy of seven or eight, my mother once said to me: "I’m fine with you doing all sports except motorcycling and mountaineering." When I asked her what that last one meant, she added: "It’s a stupid sport where you climb rocks with your hands, feet, and teeth!"

That was enough to spark young Lionel’s curiosity. From a good family in Grenoble, his early climbing feats didn’t necessarily point him toward an alpine path.

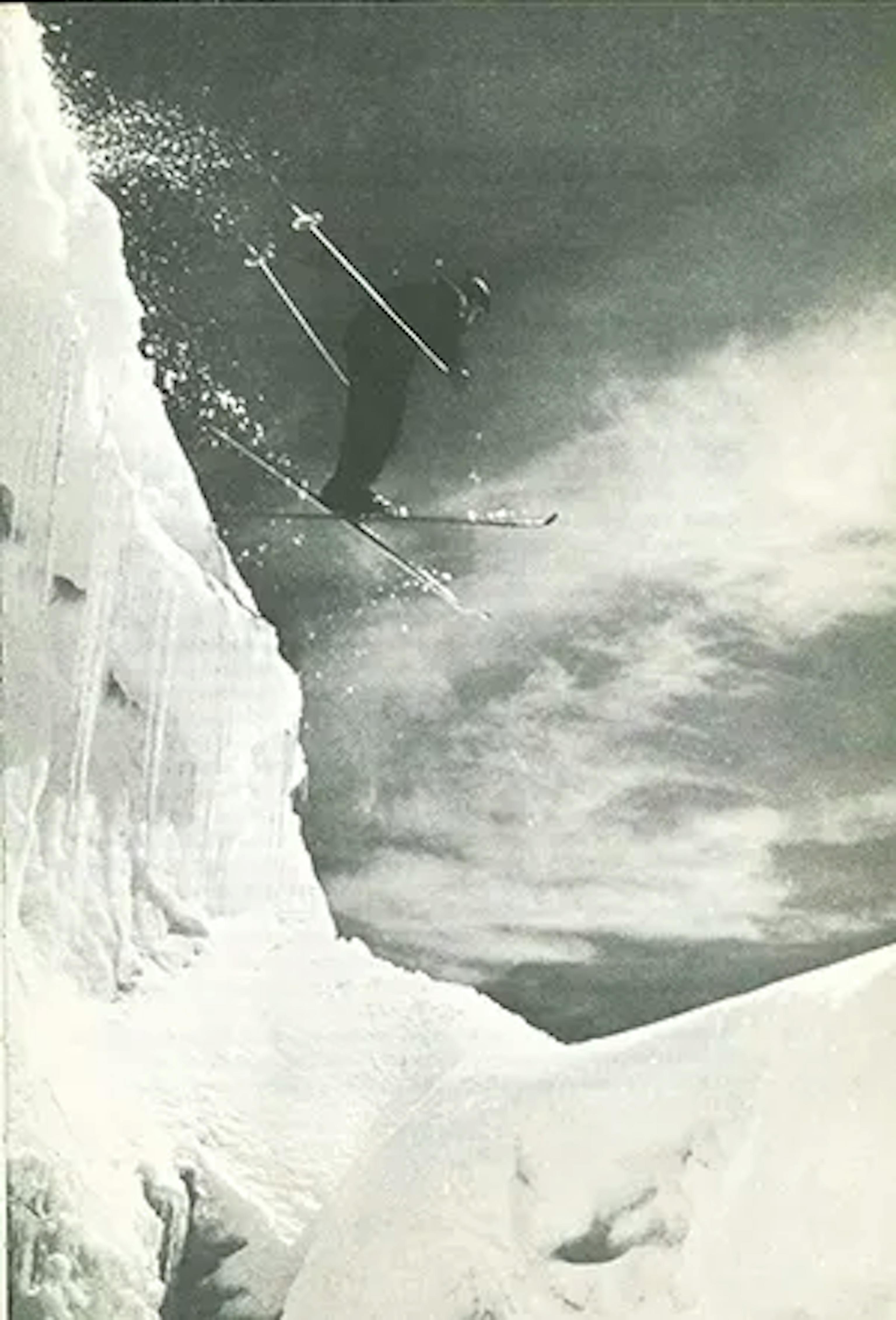

He truly excelled on skis. Because his brother was in fragile health, the family moved for a while to Chamonix to be closer to the sanatorium where he was receiving treatment.

Lionel competed in alpine ski races and also worked as a ski instructor, which provided him a modest income.

When World War II broke out, leisure activities suffered — and so did the income of those who depended on them. In 1941, he joined a military-style civil service program called “Jeunesse et Montagne” almost by default, for the small salary and especially to stay close to the mountains. That’s where he met Louis Lachenal and Gaston Rébuffat, who became key climbing partners and with whom he would go on to achieve incredible feats. In 1942, the Stéphane company (a commando-type mountain infantry unit) called on his services.

Armed with the experience gained through the military, Lionel went on to achieve numerous record-time ascents in the Alps with Louis Lachenal after the war. Their exploits slowly gained recognition, especially after the second ascent of the Eigerwand’s north face (Swiss Alps), when the press began to take notice. As an instructor at EMHM (Military High Mountain School) and later ENSA (National Ski and Mountaineering School), he decided to become a full-time guide in 1949 to gain the independence he valued so highly.

My father […] I heard him say a hundred times: "You’d have to be a complete idiot to bust your butt climbing a mountain, risking your neck, when there’s not even a hundred-franc note to be picked up at the summit"

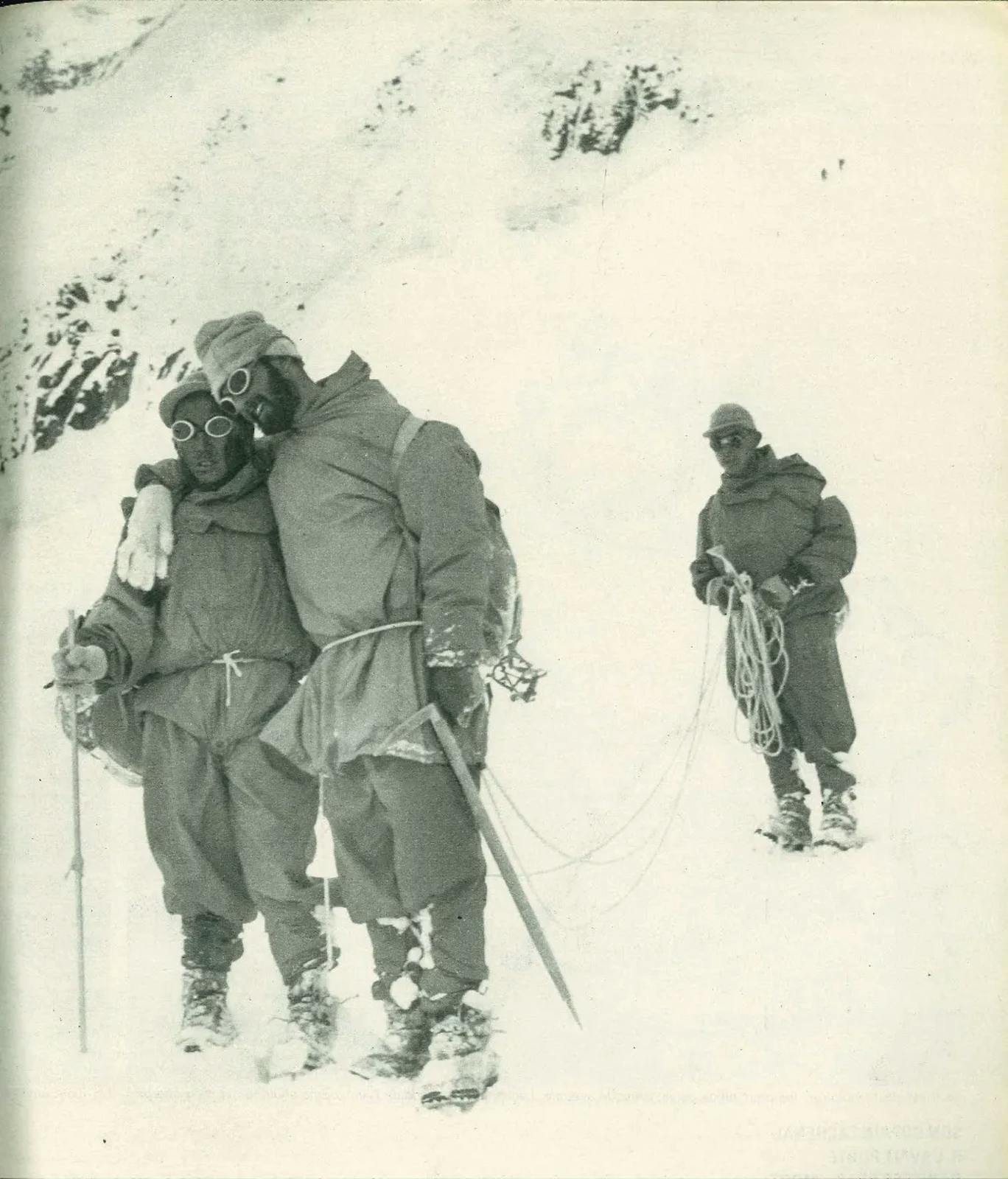

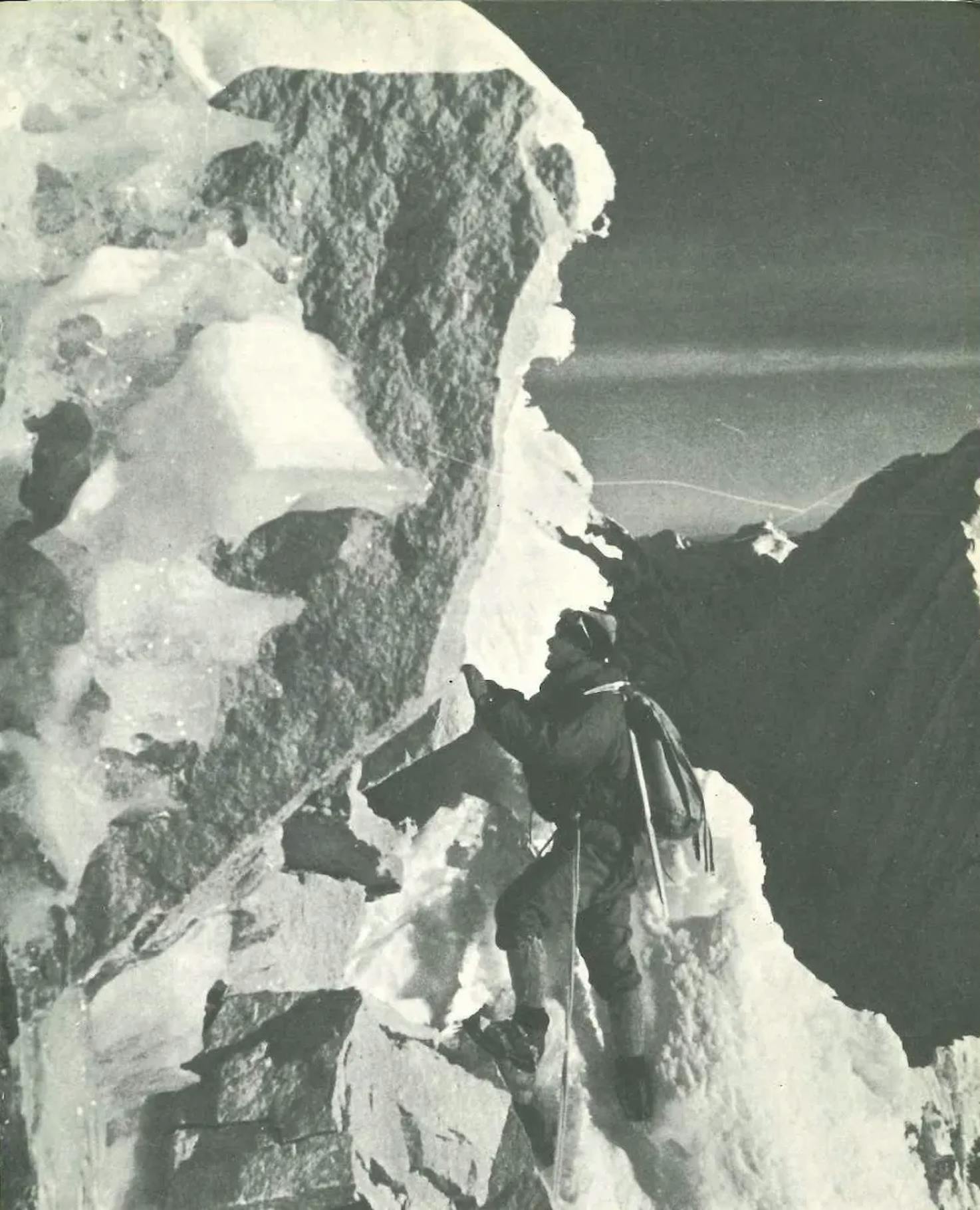

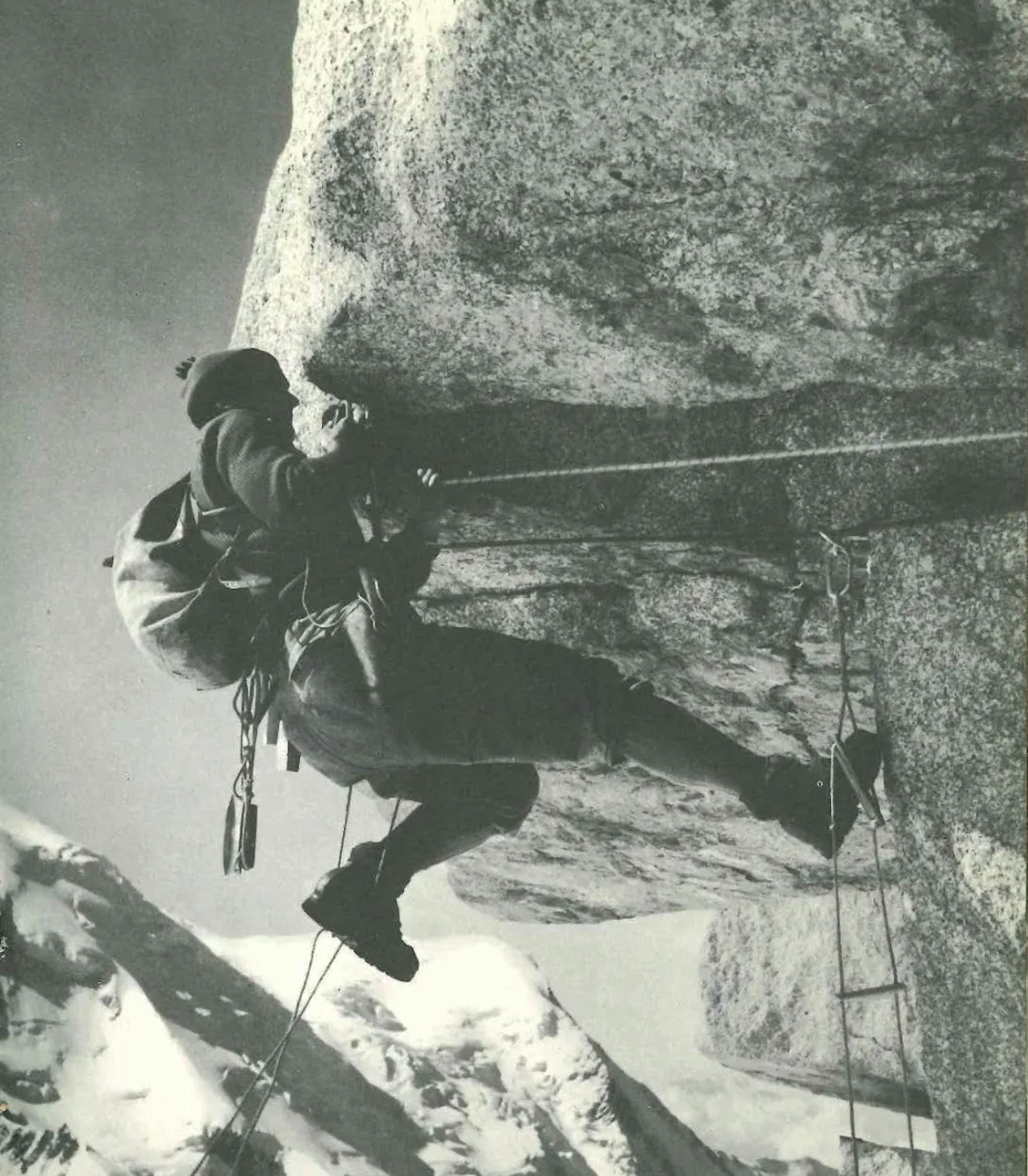

In 1950, thanks to government-funded national expeditions, Lionel set out for the Himalayas. He was part of the successful expedition led by Maurice Herzog, alongside Rébuffat and Lachenal. The goal was clear: conquer the first 8000-meter peak, which they did with Annapurna. Lionel would later summit other peaks still renowned and feared today — Fitz Roy in Patagonia, Mount Jannu and Makalu in the Himalayas, Taullirju and Chacraraju in the Andes…

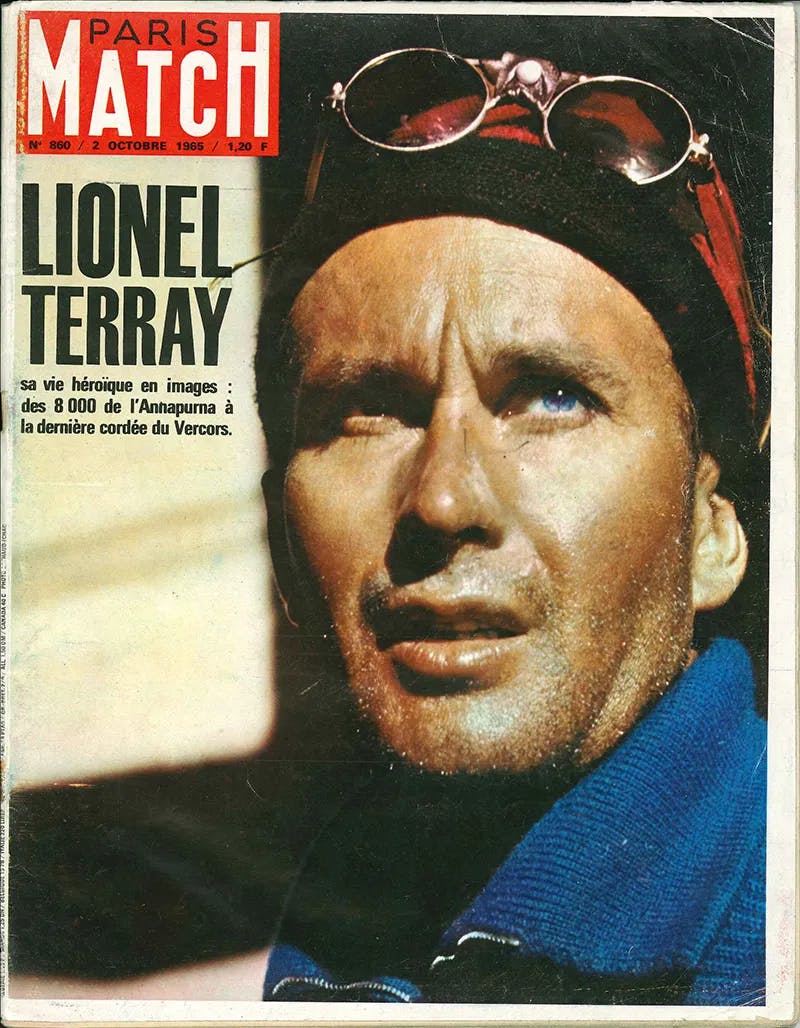

That iconic image upon returning from the Annapurna expedition made the rounds of the world. His clothing style didn’t go unnoticed — always topped with his signature red beanie and sunglasses fixed on his forehead or nose, that’s how the public got to know this alpinist. His legacy is impressive — his skiing and climbing talents can be seen in documentaries and mountain films like “Étoile du Midi” and “La Grande Descente.” The latter recounts the first ski descent of Mont Blanc’s north face in 1952.

Lionel was also known for his generosity, never hesitating to risk his own safety to rescue rope partners or stranded climbers, as shown by two major rescue operations he participated in — or even organized — in 1957 on the Eiger and Mont Blanc.

If truly no stone, no serac, no crevasse awaits me somewhere in the world to end my run, then a day will come, when I’m old and weary, and I will know how to find peace among the animals and the flowers. The circle will be complete — I will finally be the humble shepherd I dreamed of being as a child...

Lionel Terray died accidentally on September 19, 1965, in the Vercors, at the Arêtes du Gerbier. Paris Match dedicated its cover and a twenty-page article to him in the October 2 issue of the same year.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lionel Terray Les conquérants de l’inutile Edition Paulsen

Gaston Rébuffat Entre Terre et Ciel

Maurice Herzog Annapurna, premier 8000