TAKING RESPONSIBILITY FOR FAILURE, by Vivian Bruchez

Le dhaulagiri, débrief d’une « mauvaise expédition »

Champions succeed at everything they do. And that’s how we recognize them.

Except that in reality, champions sometimes fail too. And that’s why we admire them. Because they pick themselves up to be stronger and more determined than before. And quite simply better.

Vivian Bruchez is made of this stuff. A champion who succeeds so regularly that he makes his sport of steep slope skiing look easy. A champion who, together with his climbing party of Mathéo Jacquemoud, Mathieu Maynadier and Michael Arnold, has just failed in their attempt to make the first ever ski descent of the Nepalese mountain Dhaulagiri, the 7th highest peak in the world, standing at 8,167 meters. Dignified, honest and vulnerable, the virtuoso of vertiginous lines gives us an authentic report and a self-critical reading of what he considers to be a “bad expedition”. In essence, why it happened and why it won’t happen again.

Champions take responsibility for everything. Even failure. So they can turn it into a positive and constructive learning experience. And that’s how we recognize them. An open-hearted account.

BAD EXPEDITION, DIGESTION & SOFA

Vivian, why did you feel the urge and the need to speak up?

This expedition was a failure. It would have been easy to say we weren’t responsible and that it was caused by the poor weather conditions. That would be lying. We had a bad expedition. We have to take responsibility for it. It would have been more comfortable to push it under the carpet, to hide it away under the sofa, but communicating and trying to analyze it is a way of putting an end to – or who knows, suspending – the adventure.

The expedition started in September, you returned at the beginning of October and we’re now at the end of November. Why take such a long time to talk about it?

I had to digest things. I came back in a state of high anxiety and was totally drained mentally and emotionally. I was a bag of nerves. I took time to get back to a calmer and more lucid place so I could think more clearly. We were a team of four in Nepal, so it was also important for us to debrief together. Even though the project was a failure, there’s still great respect and a sense of deep kindness between us. Mathéo, “Mémé” (Mathieu Maynadier), Michael and I experienced and shared something very powerful.

You described your adventure as a “bad expedition”. Those are strong words. What does a bad expedition look like?

For me – and this is a feeling shared by my friends – the expedition was a failure because we didn’t really enjoy it. The success of a trip like this isn’t in any way determined by whether you manage to make a summit or not. In fact, quite the contrary. I’ve had to abandon missions in the past. It even happens quite often, and I don’t have a problem with it. I always learn from it. But in this case, from an overall point of view, we weren’t up to scratch when it came to all the important steps: the preparation, the approach and our actions.

CORNERSTONE, SIGNS & PREPARATION

Let’s start with the preparation. In what way do you feel it was less than optimal?

Firstly, the excursion should have taken place three years ago. Unfortunately, in 2020, Covid prevented it from happening. In 2021, Léo (Slemett) tore his cruciate ligament. And in 2022, again Léo, who was the cornerstone of our team, had to deal with a personal tragedy that had a huge impact on all of us. It was as if the expedition wasn’t actually meant to happen. I’m not superstitious. But I do pay a lot of attention to signs. I’m very much guided by my feelings, and even before the start, those feelings were very mixed. I felt we were in an in-between place, torn between doubt on the one hand, and on the other, a magnificent opportunity combined with a commitment to ourselves and our sponsors.

Could we say that something wasn’t quite right from the start of the project?

No, everything was OK. In fact, it was things looking good, and unexpected lucky encounters, that encouraged us all to climb into the same boat. While Mathéo and I were working on the project ’Un Printemps suspendu’ (A Suspended Spring), we came up with the goal of doing an “8000” in two weeks. We then meet Léo in the streets of Chamonix who told us he was preparing for the first ski descent of Dhaulagiri in Nepal, together with “Mémé” and Aurélien Ducroz. So we thought it would be cool to all go together. Except that in the meantime, we lost Léo, the driving and unifying force of the adventure. Looking back, it’s obvious that we really missed his presence. (Pauses to reflect) All the uncertainty around the departure was difficult to cope with. So we were already setting off with a lot of mental fatigue. We got the feeling it was going to be hard, but we couldn’t tell each other that. We couldn’t verbalize it.

So in a sense did the expedition happen because you couldn’t say no?

Yes, from my point of view, I agree with that: the expedition happened because we couldn’t say no before we left! Out of respect for the friends who’d worked on it, especially Mémé. Out of loyalty to the sponsors supporting us. Out of a sense that it was the easiest thing to do. It was simpler to convince ourselves it was going to work, when deep down we knew certain essential ingredients were missing... Usually in the world of mountaineering, we have to make decisions on whether to abandon much later in the process, once we’re actually on the terrain. This time, we should have abandoned before we even left. We lacked the judgement to see it.

BASE CAMP, FEAR & MINDSET

Can you tell us about your adventures while you were there?

As soon as we arrived in Kathmandu, we were faced with bad weather. We very quickly realized there was no point going to base camp, and that it would be better to do our acclimatization phase in the neighboring Langtang valley, where we’d be much less affected by the rain and could at least do a bit of trekking. We then took advantage of a lull in the weather to move closer to Dhaulagiri.

So at some point, did you start to feel hopeful again about successfully completing the first ski descent of Dhaulagiri?

Yes, hope returned when we got to the foot of Dhaulagiri. On the first day, we were treated to great conditions, allowing us to carry out a first reconnaissance mission and reach Camp II at 6,100 m. We really enjoyed ourselves that day. I thought: “Wow, we’ve got what we need to be able to do this!” Unfortunately, our enthusiasm was quickly dampened by the weather conditions over the next few days which forced us into our tents.

What did you think about during those long hours in the tent? How did you spend your time?

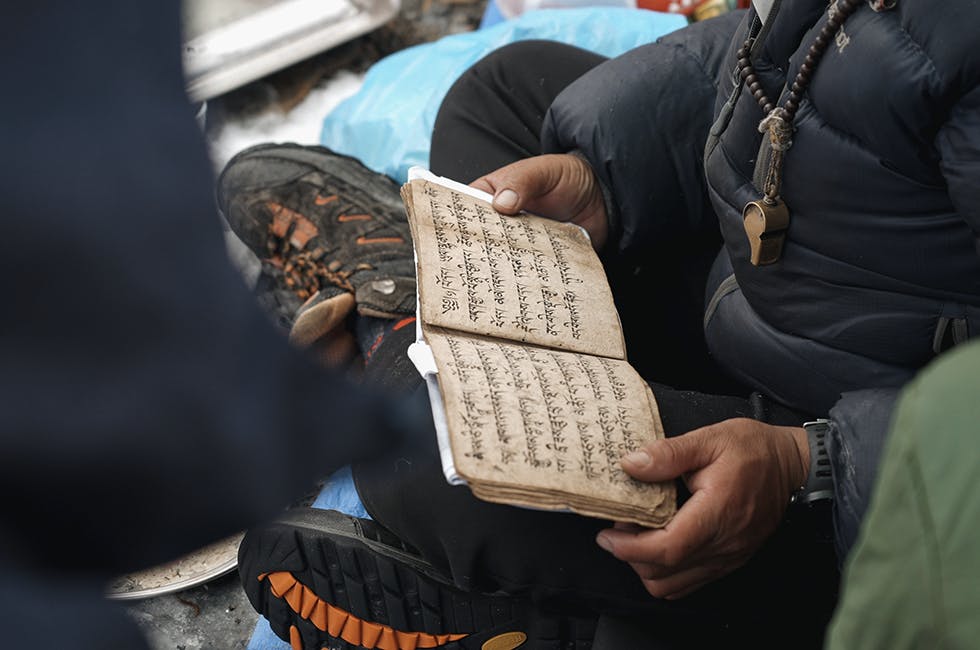

Firstly, the nights are mega-long! We fell asleep at 7 pm and woke at 6 am. We slept very well, with our sleep only disturbed by some lingering doubts. During the day, we occupied ourselves as best we could. We tried to go for short walks around the camp but were soon forced back by rain or snow. So we’d go back to the tent and wait and talk... Personally I didn’t feel like reading or writing, so I spent a lot of time brooding. That being said, the waiting time was extremely short compared to most expeditions. Being holed up for a week because of the weather is nothing, it’s common even! I just wasn’t in the right mindset. And I only understood that with hindsight.

What do you mean? In what way was your mindset not right?

Mathéo and I had let ourselves be blinded by the desire to do a short expedition. Our initial aim was to achieve an “8000” in two weeks. But in the end, with Mémé and Michael, we gave ourselves a month. But limiting yourself to a timeframe like that isn’t a good way of doing things. It makes you approach the trip with a sense of urgency and can lead to frustration when things don’t go as fast as you think they should. If you set off without any pressure on the return date, that week of waiting in Kathmandu, for example, wouldn’t have made us impatient at all. You don’t feel like you’re wasting time. You use it as an opportunity to meet the people, to explore the culture. I locked myself into that way of thinking, correlating sporting performance with time. It’s not the right approach.

How do you explain this feeling of urgency, of having to do things fast, of getting to the top as quickly as possible?

It was a combination of several things. Firstly, Mathéo and I are fathers. Mathéo has just become a dad and I have two incredible little girls and a wonderful wife waiting for me at home. Your family situation inevitably has an influence on your logistics. You don’t want to be away from home for more than a month. Secondly, I think our perceptions were skewed by our habits: in the Alps, you do something super-hard for a day but then that night you get to sleep in your own bed. And thirdly, we knew that leaving in the fall involved a degree of uncertainty, and that the longer we waited, the smaller our chances of success.

TAKING IT TO THE LIMIT, VULNERABILITY & HELICOPTER

Finally, after a week at base camp, a very brief weather window opened up for you... What did you decide to do?

Mathéo and Michael (Arnold) weren’t feeling it. They wanted to leave base camp asap and decided to go back down. Mémé and I thought we’d start the ascent slowly but surely and see where it took us. I still had that slope between Camp II and Camp III in the back of my mind... We climbed up to an ideally placed col at around 6,000 m. Unfortunately, the weather deteriorated very quickly and we were suddenly stuck with no real possibility of going higher. So I spent a horrible night, locked inside my anxieties. I was mad at myself. I wondered what the hell I was doing there. Why hadn’t I followed Mathéo and Michael? I preach caution on a daily basis and there I was, trapped.

How did you get out of that nightmare?

In the early morning, a tiny window opened up for us, with a way back down. We had to seize it at all costs because 10 days of storms had just been forecast. We roped up and put on our skins to ski back down because visibility was really poor in foggy conditions. But the first time the skies cleared we realised that we were right under huge slopes that threatened to come crashing down on us. We had no other choice but to go back up. There was a clear sense of death in the air.

And then you got a massive piece of luck...

Yes, we did. We heard the helicopter that was taking climbers back to Kathmandu arrive at base camp. We saw the sky was clear and that they had a window to come and pick us up. There was absolutely no hesitation. It was no longer a question of risk management but of survival. We grabbed the radio and asked them if they could come to our rescue. Michael, who was still at camp, took matters into his own hands and spoke with the pilot. He did an amazing job. They got Mémé and I out of there.

We know you’re very careful about minimizing risk for yourself and others. How did you feel about having to take the helicopter?

I thought: “Goddammit, I can’t believe it! I’ve never been stranded like this in the Alps, and now, for something I’ve had my doubts about for months, I end up having to call for help.” I was so mad at myself. But you have to take responsibility for it.

Have you ever felt so vulnerable?

No, I don’t think so. At least, I’ve never faced such a build-up of emotional fatigue. I lost it. I reached the most extreme point of fear because I was mentally exhausted. We were in a very bad situation, but with hindsight, in the Alps, I could have got myself together again, and waited for the heat to purge that east face. Unfortunately, over there, I no longer had the resources. I’d already blown everything a good while back!

Did you cry?

Yes. Twice. First in the helicopter. And then when we got back to Mathéo and Michael at base camp. Later Michael told me that when they picked me up, I looked like a ghost. I let it all out. I couldn’t take any more.

Looking back, what lessons did you learn from the expedition?

Lots of different ones. You learn many things from failure. To start with, to know how to say no earlier on. To think more carefully about projects by looking inside myself to work out whether, yes or no, they excite me, whether they light a little flame deep inside me. And then to make each project the result of a proper, highly personal, carefully constructed process. I need to do it like that to feel fully involved. So I wouldn’t want to repeat leaving with such a large party for such a challenging expedition. It can turn out to be a great strength but also lead to a form of inertia. Either way, you need a leader. Lastly, this has caused me to really question myself, like an athlete who takes a massive hit after a poor performance. I realized that I wasn’t up to it physically, that I was no longer athletic enough. The failure of the expedition acted like a detonator. It motivated me like never before. Not to ski – I don’t need to be motivated for that – but to become better. My partners support me to be an athlete. So what do athletes do? They train so they can perform.